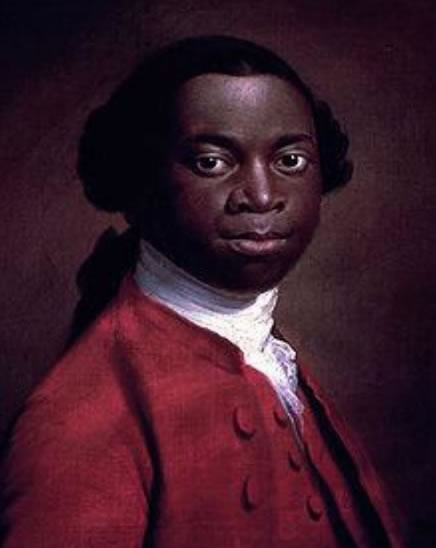

Olaudah Equiano was born about 1745 of Igbo parents in a village he called “Essaka, near Benin”, which has been identified as Iseke in Ihiala local government area of Anambra State. This identification was done by the late Catherine Acholonu in a work of remarkable scholarship. ‘Equiano’ was probably a corruption of ‘Ekweano’, with the corruption attributable to the long interval between his capture as a boy of about 12 and the time of his writing more than thirty years later, without interval contact with his original home. Additionally, he might have needed to ‘anglicise’ words for easier pronunciation and benefit of his mainly English readers, some of whom were his patrons and sponsors.

He was the second youngest of seven siblings: five brothers and a younger sister who was kidnapped with him by the slave raiders. His father was one of the local titled elders who settled disputes in the community. When he was about twelve, Equiano and his sister were abducted by slave raiders when the parents were away from home. They were sold to slave traders and after six months of captivity, their party was brought to the seacoast where he encountered Europeans for the first time. He later recalled in his autobiography:

“The first object which saluted my eyes when I arrived on the coast was the sea, and a slave ship, which was then riding at anchor, and waiting for its cargo. These filled me with astonishment, which was soon converted into terror, when I was carried on board. I was immediately handled, and tossed up to see if I were sound, by some of the crew; and I was now persuaded that I had gotten into a world of bad spirits, and that they were going to kill me……..such were the horrors of my views and fears at the moment, that, if ten thousand worlds had been my own, I would have freely parted with them all to have exchanged my condition with that of the meanest slave in my own country.”

He was placed on a slave-ship bound for Barbados and described his initiation to this new abode thus:

“I was soon put down under the decks, and there I received such a greeting in my nostrils as I had never experienced in my life; so that, with the loathsomeness of the stench, and crying together, I became so sick and low that I was not able to eat, nor had I the least desire to taste anything. I now wished for the last friend, death, to relieve me; but soon, to my grief, two of the white men offered me eatables; and, on my refusing to eat, one of them held me fast by the hands, and laid me across, I think, the windlass, and tied my feet, while the other flogged me severely. The closeness of the place, and the heat of the climate, added to the number in the ship, which was so crowded that each had scarcely room to turn himself, almost suffocated us. The air soon became unfit for respiration, from a variety of loathsome smells, and brought on a sickness among the slaves, of which many died. The wretched situation was again aggravated by the chains, now unsupportable, and the filth of the necessary tubs, into which the children often fell, and were almost suffocated. The shrieks of the women, and the groans of the dying, rendered the whole a scene of horror almost inconceivable.”

His first owner who bought him in Barbados was one Jacob who named him after himself. After a two-week stay in the West Indies where he could not be resold because of his youth, Equiano was sent to the English colony of Virginia in the USA where in 1754 he was purchased by Captain Henry Michael Pascal, a British merchant naval officer. He gave him the new Latinised name of Gustavus Vassa in honour of the Swedish king whom he admired. (Renaming of slaves was quite a common practice at the time, but Equiano did not accept his new name meekly). When he resisted it, wanting to hold on to the first given name of Jacob, it “gained me many a cuff,” – he was slapped, smacked, and beaten before he eventually submitted. Of this period in Virginia he would later write about the cruelty with which house slaves were treated, for example the use of iron muzzles which barely allowed them to speak, eat or drink, to keep them quiet as punishment. The new owner later took him back to England with him.

For seven years he served on British ships as Pascal’s slave, participating in or witnessing several battles of the

Seven Years’ War. Fellow sailors taught him to read and write and to understand mathematics. He was also

converted to Christianity……..finally opting for Methodism.

By the end of the Seven Years’ War he had reached the rank of able seaman. Although he was Pascal’s servant, he had helped in the war effort by hauling gunpowder on to the deck but did not receive any share of the war booty like other (free) seamen after Britain won the war; Pascal kept Equiano’s prize money from this war service. He however granted him the favour of learning to read and write better through the efforts of his sister and her friends. Equiano was baptised at St Margaret’s Church Westminster, London, in early 1759. Pascal had promised him his freedom but later reneged on this, apparently as some people claimed, because of his own declining fortunes. Instead he sold him in 1762 to Captain James Doran of Gravesend (U.K.) who was returning to the Caribbean as master of the ship Charming Sally. Equiano himself later wrote that Pascal had instructed Doran to ensure that he was sold:

…to the best master he could get, as he told him I was a very deserving boy, which Captain Doran said he found to be true.

Charming Sally subsequently landed in Montserrat where he was sold to Robert King, a Quaker merchant of Philadelphia, USA. Equiano was set to work on his new master’s stores and on their shipping routes between the Caribbean and Philadelphia. He so impressed his master that he helped him improve on his literacy, mathematics, and basic tenets of Christianity. He allowed him to trade for himself while still working for him and promised him his freedom for the same amount of forty pounds (£40.00) that he had paid for him. Equiano was astute enough to save up this sum soon afterwards, to the surprise of his master who later said that he had made the offer because he had thought he could not attain it! But he kept his word, so Equiano bought his freedom in 1766, aged about 23. He turned down the offer of a trading partnership with his former master because he considered it too dangerous for his freedom. Indeed, once after his freedom, while loading a ship in Georgia which was another British colony in the USA, he was kidnapped and almost sold back into slavery. He was freed only after he proved his education and freed status, with the help of documents and some well-meaning friends. He preferred instead to head for Britain where a famous case in the courts lessened the risks of his reversion to slavery. This was a case in England in which a slave, James Somersett, who was bought in Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.A. by one Charles Stewart, a customs officer, was brought to England in 1769, and escaped from his master in 1771. He was subsequently recaptured, and detained on a ship, preparatory to being sent to Jamaica where he was to be sold. His three godparents, under the direction of the great abolitionist, Glenville Sharp, sued the ship’s captain John Knowles, challenging the legality of his imprisonment on the ship. The case attracted wide publicity and divided public opinion almost evenly; such was the public interest in the case that people donated large sums of money to both sides for the court hearing. The case was heard in the King’s Bench between February and May 1772 with The Chief Justice of the Bench, Lord Mansfield presiding. The court decided that slavery was not supported by existing laws in England and Wales, stating that:

The state of slavery is of such a nature that it is incapable of being introduced on any reasons, moral or political, but only by positive law, which preserves its force long after the reasons, occasions, and time itself from whence it was created, is erased from memory. It is so odious, that nothing can be suffered to support it, but positive law. Whatever inconveniences, therefore, may follow from the decision, I cannot say this case is allowed or approved by the law of England; and therefore, the black must be discharged. [Usherwood, Stephen. (1981). The Black Must Be Discharged – The Abolitionists’ Debt to Lord Mansfield History Today Volume: 31 Issue: 3. 1981

This court ruling gave a big fillip to the movement for abolition of slavery especially as a similar case (Knight v. Wedderburn) in Scotland which took place shortly afterwards, between 1774 and 1778 decided that slavery had no existence in Scottish common law. Thus by 1780, slavery was illegal in England, Wales, and Scotland, although it took nearly another 30 years (in 1807) for Parliament to legislate its abolition formally. Equiano felt bad in himself for his powerlessness to help other slaves and believed his only chance of ever being able to do so lay in his own freedom.

I was often a witness to cruelties of every kind, which were exercised on my unhappy fellow slaves. I used frequently to have different cargoes of new Negroes in my care for sale; and it was almost a constant practice with our clerks, and other whites, to commit violent depredations on the chastity of the female slaves; and these I was, though with reluctance, obliged to submit to at all times, being unable to help them.

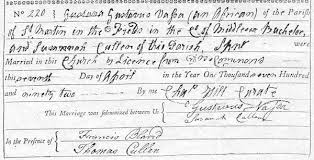

He worked closely with Granville Sharpe and Thomas Clarkson in the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade and took every opportunity to talk not only about these well publicised cases, but to share his own personal experiences. In these public meetings he described in detail, examples of the cruelty of the slave trade and the condition of slavery, with his own eye-witness accounts. These accounts were supported by those of an erstwhile slave ship captain and trader, John Newton (1725-1807), who later became converted to Christianity and eventually became an Anglican Church minister and hymn writer, with Amazing Grace being his best known hymn. He also worked closely with, and influenced William Wilberforce, encouraging him to remain in Parliament and ‘do the Lord’s work there’ instead of leaving it as he once considered, because of the difficulties and frustrations he was encountering in Parliament trying to achieve this. In addition to Amazing Grace, Newton also published later in 1788, a pamphlet, Thoughts Upon the Slave Trade, which documented his experiences of the horrors, wickedness and cruelty of the trade. In 1787 Equiano helped his friend, Offobah Cugoano, to publish an account of his experiences as, Narrative of the Enslavement of a Native of America. His efforts to use this book to get the royal family and other influential people interested in the cause of abolition failed as most of them benefited from it. So in 1789 he published his own autobiography, The Life of Olaudah Equiano the African with the help, encouragement, and financial support of some of his abolitionist friends, and a great many eminent men and women of the time. The book powerfully demonstrated the evils and inhumanity of slavery as well as showing his humanity and caring. His description of his original home life and culture also showed that his people were not the savages they were depicted as but had an ordered society and a system of governing themselves. This was different from the story of slave traders who portrayed Africans as very primitive to justify their actions and greed. He travelled throughout England promoting the book which became an instant bestseller. It was also published in Germany (1790), America (1791) and Holland (1791) and so popular was it that the English edition had many copy runs. He also spent over eight months in Ireland promoting the book; there he sold about 2000 copies and spoke widely about the evils of the slave trade. The success of the book made him more financially independent and enabled him to chart his own course without dependence on benefactors. He also used his prominence and ‘celebrity status’ to act like a voice for other black people, especially The Poor Black in London. His actions and comments were often reported in newspapers like the Public Advertiser and the Morning Chronicle whereas most other black people were treated as if they did not exist. He was a friend of the novelist, Thomas Hardy, who was at one time the secretary of the London Corresponding Society which among other things, advocated for working men to have the right to vote. Equiano supported this, as well as the extension of voting rights to women. He married Susanna Cullen (1761-1796) of Soham, Cambridgeshire on 7th April 1792 and they had two children, Anna Maria (born 1793) and Johanna (born 1795). However, Susannah died in February 1796 aged only 34 and Equiano died a year after that on 31 March 1797. He had been appointed by the British Colonial Office to the expedition to settle former black slaves in Sierra Leone, West Africa but died before he could take part in this venture. His older daughter Anna Maria died soon afterwards, aged only four years, leaving Joanna a lonely orphan. She was brought up by her mother’s relatives and later married the Rev. Henry Bromley, whom she helped to run a Congregational Chapel at Clavering near Saffron Walden in Essex. They later moved to London where she died in 1857.

Equiano’s marriage certificate

Even in death, Equiano was thinking of others rather than himself. By his will which was drawn up in 1796 after his wife’s death, he had prescribed that should none of the daughters attain the majority age of 21, half of his estate was to go to the Sierra Leone Company for “continued assistance to West Africans”, and half to the London Missionary Society, which promoted “education” overseas. The late Chinua Achebe called him “the father of African literature,” while Henry Louis Gates claimed him for America as “the founding father of the Afro-American literary tradition”. Perhaps Equiano’s most lasting and enduring legacy is giving other people and therefore us and our generation, in his writing, a first-hand eye-witness account of the horrors and depredations of slavery, as well as some account of Igbo society organisation before the era of European influence.